Global Mobilisation in the case of Contemporary Chinese Art in the 1980s-1990s

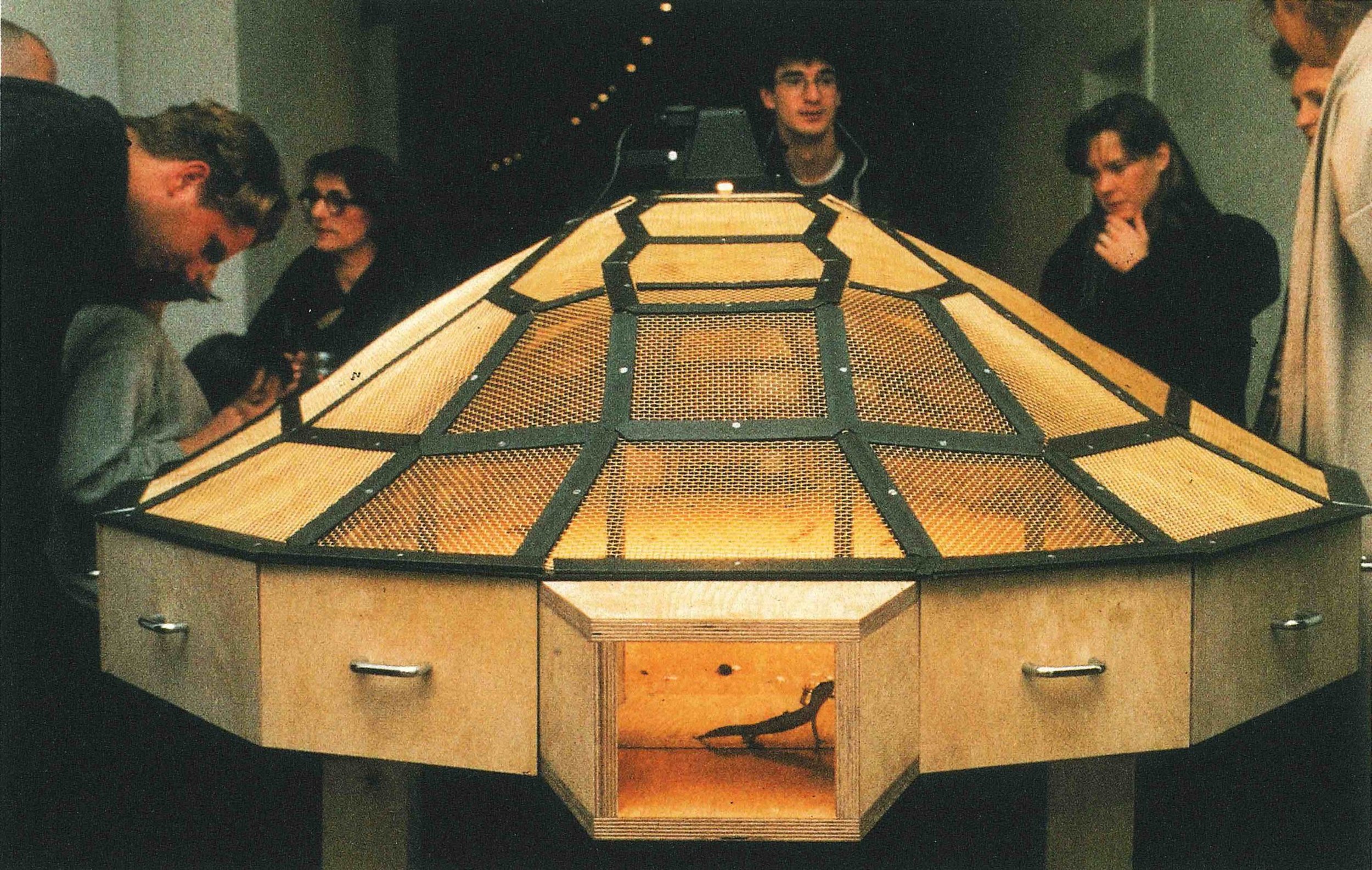

Figure 1. Huang, Yong Ping. Theatre of the World. 1993/2017. Mixed media installation, Wood and metal structure with warming lamps, electric cable, insects (spiders, scorpions, crickets, cockroaches, black beetles, stick insects, centipedes), lizards, toads, and snakes, 150 x 170 x 265 cm.

The late 1980’s and 1990’s marked a transformative moment in China’s cultural, economic, and political ecology, shapeshifted by its confrontation of ‘modern world-system’ predicated on Eurocentric modernity and globalisation[1]. Thus, the expansion of China’s cultural and economic gates mobilised a continuous flow of cultural exchange between the East and West. Contemporary Chinese Art became a popular commodity within the international art circuit, favoured as a cultural spectacle to reinforce the Cold War ideological antagonism against the ‘Communist world’. As such, the reception of contemporary Chinese artists that exhibited beyond their locality became subject to the West’s ideological imperatives and cultural fetishes. As art historian and curator Hou Hanru articulates, “Chinese characteristics have become ideal commodities for the consumer/spectacle society”[2], art in China began to hold a new status in and out of its locale. Freed from China’s political and authoritative hold on its official art discourse, Chinese contemporary artists were confronted with a new constellation of limitations and constraints from a burgeoning cultural authority of Western hegemony. Two seminal Chinese contemporary artists Xu Bing and Huang Yong Ping became interested and concerned with the burden of representation and ideologic-centrism within the international arena. Their works grappled with the Western artistic hegemony and cultural authority, questioning the over-extraction of meaning, and the strained emphasis on cultural purity and ideologic-centrism from two ideologically driven societies. Huang and Xu engaged with hybridity as a critical “third” modality to transcend the limitations of the global white cube. As academic Birgit Hopfener articulates, “Chinese contemporary artworks are understood as active agents that are entangled in the dynamic processes of globalisation”[3], Xu and Huang conjured a “glocal” language in the mid-ground between the local and global. The complex process of globalised mobility and flow of culture, ideology and visual forms have allowed critical modalities of hybridity and ‘cannibalism’ to emerge for migrant and cross-cultural artists.

Contemporary Chinese art has always been underpinned by migration, diaspora, and cross-cultural exchange. The dynamic processes of globalisation propelled a generation of Chinese artists to migrate beyond their locales towards the Western centres of art in the 1980’s and 1990’s. Born in 1954, Huang Yong Ping was one of the founders of the Xiamen Dada Chinese Avant-Garde group in the 1980’s, who sought to de-ideologicalise themselves from the dominant genre of Socialist Realism by combining the spiritual and philosophical notions of Chan Buddhism with Western Dada-ism’s rejection of dogma, text and doctrine. Xu Bing was similarly a part of the Chinese Avant-Garde Maximalist movement, who sought to de-ideologicalise China’s official art discourses and the Western emphasis on cultural difference and identity, through the dematerialisation of meaning, ideology, and text. Both Huang and Xu sought to invoke cultural critique between their local and global context, standing in the mid-ground between the East and West[4]. Following the TianAnmen Square Student Protests and Jean Hubert-Martin’s seminal multicultural show Magiciens de la Terre in 1989, Huang migrated to Paris, and in 1992, Xu migrated to New York, marking the beginning of their amphibious career as a migrant and cross-cultural artist. Both artists experienced the unstable, agitating but revolutionary moments of history between China’s post-Cultural Revolution and the post-Cold War globalisation, hybridising the cultural moments from their turbulent environments. Academic Nikos Papastergiadis highlights those migrant and cross-cultural artists have learnt to engage with hybridity as a critical modality to transcend the limitations of cultural dualisms and ideological centrism[5]. The mobilised experience of “being insiders and outsiders to several cultures and societies at the same time”[6] profoundly shaped the artistic careers and expressions of these artists. Many artists sought to respond to the othering expectations of the international market, by unsettling the Western centric modes of interpretation through deconstructing ideologies and hybridising artistic methodologies[7]. Rearticulating the polarities of ‘in’ and ‘out’, Xu and Huang conjured a ‘glocal’ and amphibious practice that negotiated and mediated both the local and global, forging a new artistic landscape within the international arena.

The dynamic process of globalisation for Chinese artists came with the confrontation of Western capitalism, and the flow of Western economic powers into China’s local arts ecology and market. Since the Economic Reform in 1978, Political Pop and Cynical Realism became the popular ‘unofficial’ art style, poised against the ‘official art discourse’ of Socialist Realism in China. Cultural theorist Slavoj Žižek describes this phenomenon as ‘kynicism’, wherein the rejection of the official culture is exercised through “pathetic phrases of the ruling official ideology”, everyday banality and cynicism[8]. Therefore, ideology became a fundamental concern for both Chinese contemporary artists and the international art market, as “it became the most easily grasped key for an international public to open the door towards acknowledging and understanding the present situation of China’s reality, culture and art”[9]. Profoundly influenced by the Cold War ideological antagonism of the East and West binary, Western institutions and media sought for ideologically driven images and exotic characteristics for presentation to the Western spectacle society[10]. Art historian David Clarke illuminates in the context of Political Pop artist, Wang Guang Yi’s reception in the international market, the West has long since been engaging with reductive readings and cultural fetishism of Chinese art, using it to reinforce the cold war ideology and Western centric cultural viewpoints[11]. This marked a critical moment for the reception of contemporary Chinese art, and its demanded essentialist exoticism for “images of ‘unofficial art’ in a Communist society”[12] for Western consumption and spectacularisation. As new visual information is transmitted and mobilised across diverse locales, it is critical to acknowledge the significance of “repositioning the core/periphery model in order to indicate that Euro-American is not always the central axis around which all cultural activity rotates”[13]. Breaking away from two ideologically driven societies at the beginning of globalisation, Huang and Xu sought to rearticulate the perceptions of contemporary Chinese art towards the search for new ‘un-unofficial’ artistic languages and modalities on a global scale.

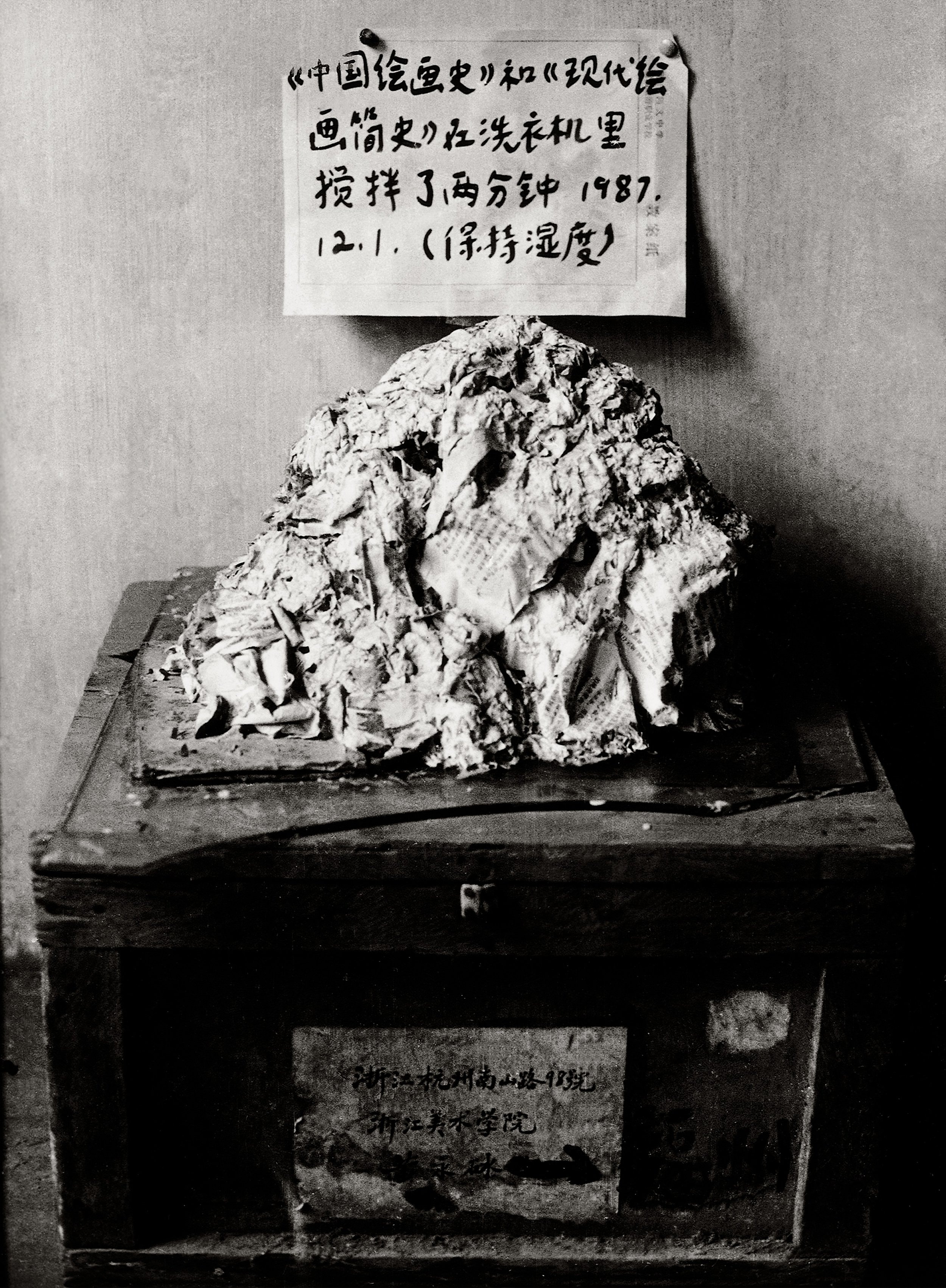

Figure 2. Huang, Yong Ping. The History of Chinese Art and A Concise History of Modern Painting Washed in the Washing Machine for Two Minutes

《中国绘画史》和《现代绘画简史》在洗衣机里搅拌了两分钟. 1987. Installation, Chinese tea crate, paper pulp, glass, 76.8 x 48.3 x 69.9 cm. I

The reception of Chinese contemporary art in the 1980’s and 1990’s was underpinned by the expansion and mobilisation of China's economy into the international arena, confronted with a double-edged sword of traditionalism and modernism. Questioning the definition of art and the timeline of art histories within both Western and Chinese art discourses, Huang’s transformative readymade The History of Chinese Art and A Concise History of Modern Painting Washed in the Washing Machine for Two Minutes 《中国绘画史》和《现代绘画简史》在洗衣机里搅拌了两分钟 (1987) (see Figure 1), illuminates what contemporary Chinese artists grappled with at the beginning of China’s economic and cultural reform. Huang washed Wang Bomin’s History of Chinese Painting (1982) and Herbert Read’s A Concise History of Modern Painting (1959), which was also the first history of modern Western art translated into Chinese, in a washing machine for two minutes. The two canonical texts are representative of two very different cultural truths and purity. Combining the forces of these two cultural canons of artistic ‘purity’ and ‘truth’ into a homogenised and unidentifiable paper pulp placed on top of a Chinese tea crate. The Chinese tea crate is symbolic of the flow of trade and cultural exchange between the East and West. Huang embodies the cultural collision within China’s arts ecology as Western cultural and political influences began to trickle into China. Art history has always been written and dictated by agents of power and authority, Huang's work questions the cultural power of who decides the meaning of such notions of ‘truth’[14] challenging the centre/periphery model in art history writing. The meaning of ‘xí 洗’ (washing) in Chinese also elucidates to the process of ‘purification’ and ‘indoctrination’. This double entendre is indicative of the tensions of negotiating between traditionalism and modernism, communism and capitalism, East and West. Through this performative action of ‘ xí 洗’, Huang challenges the historical authority and questions contemporary power relations within cross-cultural exchange. The reception of Chinese contemporary art within the West was bound to essentialist Western expectations of the ‘orient’, driving contemporary Chinese artists as the ‘Other’ in the international discourse [15]. As cultural theorist Anne Ring Petersen affirms, “hybridity is not a new form of virtue and purity”[16], driven by connection and separation Huang complexifies the definitions of art by rendering the cultural opuses to an unimaginative congealed lump. The reductive essentialism of the Western art market drove Huang to deconstruct the cultural power and authority both texts withhold, creating an entropy, disturbing the East and West’s dichotomous relationship.

Figure 3. Xu, Bing. Case of Transference 《一个转换案例的研究》. 1994. Performative mixed media installation with ink, pigs, and books.

In the same way, the emphasis on meaning and ideological demands from both the East and West have also driven artists like Xu Bing to transcend the demands of absolute truth and meaning. Akin to Huang, Xu sought for new artistic languages beyond the official and un-official artistic modalities, through performative and temporal works. As a result of the Cultural Revolution, artists borrowed the ‘fragmentation of language’[17] from Mao ZeDong’s ‘Anti-Spiritualist Campaign’ from 1983-85. The campaign brought about rampant destruction of bourgeois cultural production and Western Abstract-Expressionism[18]. From the mid-1980’s performance art was one of the favoured artistic modalities adopted for its confrontational factor[19]. Clearly breaking away from Socialist Realism, Political Pop and Cynical Realist paintings, Xu’s 1994 performative work involving pigs was one of the most controversial works made in the early 1990’s. Attempting to raise questions about the East-West cultural collision and confrontation, Case of Transference 《一个转换案例的研究》 (1994) (see Figure 3) was a performance work involving two pigs mating in a gallery space in Beijing, both stamped with nonsensical English and meaningless Chinese characters respectively. The pigs were penned in the gallery space by a crowd of viewers with the floors canvased by books written in both English and Chinese. Art researcher Jeanne Boden described the performative work as “the most primal form of social intercourse”[20], wherein the two creatures embody two cultures colliding together. The entangling and dominating process of globalisation is embodied through the nonsensical-English stamped boar copulating with the pseudo-Chinese stamped sow, taking the dominant position as witnessed by all the viewers. This act of ‘cultural assault’ can be interpreted as the sweeping domination of Western capitalism, cultural influences, and ideologies into China’s local arts ecology. However, despite the possible interpretations of the work as commentary on the Western domination of China’s cultural dialogue, Xu sought for a less humanist intention. Xu remarks that “people and pigs are completely the same, except culture has changed people”[21]. With that in mind, Case of Transference unveils the repressive and divisive nature of culture and ideology. This powerful performance underscores the over-emphasis of meaning within, doing so through its symbolic juxtaposition, entailing the beginning of Xu’s amphibious artistic career as a migrant and cross-cultural artist in New York. Both Xu Bing and Huang Yong Ping extract all meaning and significance of both languages and cultures to de-territorialise their work from dualistic paradigms of culture, creating an entropy of in-betweenness amid the East and West.

Hybridity is a critical modality and aesthetic that has been used by migrant and cross-cultural artists to negotiate with cultural differences within the context of globalisation and the mobilised art world. Homi K. Bhabha reminds us that cultural identity has been a transformative, temporal, and performative process[22], this rings particularly true as art and cultural influences have become mobilised beyond borders. Huang’s The History of Chinese Art and A Concise History of Modern Painting Washed in the Washing Machine for Two Minutes is indicative of the transformative epoch towards the end of the twentieth century in China, as artists began to grapple with the tensions between Chinese traditionalism, Social Realism, political cynicism, and Western modernism. The mobilisation of artistic influences and cultural ideology across borders have reinforced notions of identity dualism for many contemporary Chinese artists[23]. Bound to idealist spatial attachments to a fixed locality, migrant artists are urged to perform exoticised cultural characteristics and expression for new opportunities and recognition from the international market. As Papastergiadis defines, hybridity emerges from the “disruption of the exclusionary structures of global culture”[24]. This can be relativised to how Huang challenges the definitions of contemporary art by deconstructing these structures towards a new sort of global hybridised art. Akin to Case of Transference, Xu also engages with hybridity to express the underlying tensions of being a migrant artist confronting Western globalisation. Both Huang and Xu engaged with hybridity in a transformative sense, allowing for what Bhabha articulates as “cultural enunciation” within an in-between ambivalent space[25]. Likewise to their migratory and amphibious artistic practices, the “migratory nature of visual forms manifests itself in multifarious ways” [26], challenging the stagnant binary that contains the meaning of their artworks and identity to dualistic attachments to geography and nationhood. This rings particularly true for artists like Huang and Xu who must grapple with exhibiting and circulating their works in new locales within the Western capitalist circuit.

Figure 4. Xu, Bing. Square Word Calligraphy Classroom《英文方块字书法入门》. 1994-1996. Mixed-media installation; instructional video, model books, copybooks, ink, brushes, brush stands, blackboard

The forces of migration, connection, and displacement allow for critical hybrid modalities to emerge for migratory and cross-cultural artists to enunciate at the liminal threshold of the East and West. As “visual forms and images are themselves migrating phenomena”[27], artists have sought to borrow, appropriate, juxtapose, and hybridise cross-cultural imagery to unsettle essentialist modes of interpretation. Xu Bing’s calligraphic writing system and installation Square Word Calligraphy Classroom《英文方块字书法入门》 (1994-1996) (see Figure 4) profoundly hybridises the writing forms and systems of Chinese characters and English words. Xu demystifies calligraphy by hybridising the pictorial writing systems of Chinese with English letters composed in the form of a square. The pedagogical installation has appeared across several Euro-American ‘centers’ of art such as Munich, Uppsala, Copenhagen, Berlin, Johannesburg, New York, Sydney, and France as classroom workshops teaching the Square Word Calligraphy writing system (see Figure 5). Likewise to Case of Transference and Huang’s The History of Chinese Art and A Concise History of Modern Painting Washed in the Washing Machine for Two Minutes, Xu illuminates and demystifies the intricate and profound relationship between language and power. Breaking away from linguistic traditions of both English and Chinese, he asks viewers to study and expand their conceptions of ‘authentic’ culture and essentialist stereotypes[28]. Xu’s artistic practice can be characterised as Stine Høholt’s understanding of ‘cannibalistic’ within the context of contemporary artistic practices in India. Hohølt characterises cultural cannibalism as a method of entanglement often employed by mobilised contemporary Indian artists, where symbolisms, techniques, and elements of other (often dominant) cultures are entangled with symbols from their own to cultivate a new system of meaning making[29]. Offering a disruptive experience but unlimited possibilities, Square Word Calligraphy undermines and demystifies English as the ‘global language’ and de-territorialises our understanding of language and its relationship with geography, ethnicity, and culture. This hybrid modality and aesthetic expands the possibilities for criticality and “help[s] focus our understanding of diverse responses to the question of cultural difference”[30] within the global circuit. Again, Xu engineers a polarising interaction to subvert the entangling expectations from the double-edged sword of globalisation. This cross-cultural hybrid aesthetic has become a common condition for migrant artists who work amphibious careers within many locales. Xu’s oeuvre illustrates how a hybrid modality influenced by ceaseless movement can transcend the othering paradigms of cultural understanding.

Figure 5. Xu, Bing. Square Word Calligraphy Classroom《英文方块字书法入门. 1994-1996. Mixed-media installation; instructional video, model books, copybooks, ink, brushes, brush stands, blackboard.

Figure 6. Huang, Yong Ping. Theatre of the World. 1993/2017. Mixed media installation, Wood and metal structure with warming lamps, electric cable, insects (spiders, scorpions, crickets, cockroaches, black beetles, stick insects, centipedes), lizards, toads, and snakes, 150 x 170 x 265 cm.

Ideologically, the Western hegemony continues to be the strong arm of global mass culture, wherein the mobilisation of cultural identity and translation are still underpinned by uneven power dynamics. Huang Yong Ping radically extended his sceptical insights into global mass culture as a cross-cultural artist through his ontological research and existential synthesis. Akin to Xu’s provocative performative works, Huang’s 2017 remake of his 1993 ‘living’ installation Theatre of the World (1993/2017) (see Figure 6 & 7) sought to unveil the continuing cannibalistic reality of the global art circuit experienced as a Chinese contemporary artist. By creating a giant metal and wood, gladiatorial like enclosure where spiders, lizards, turtles, scorpions, crickets, cockroaches, centipedes, snakes, and toads were brought together to co-exist, conjuring an artificial ecological environment of survival. The insects and animals were expected to feed on each other and be replaced throughout the duration of the work, as viewers observed and witnessed life within the cage. Huang’s ecological prison alluded to the panoptic spectacle of the globalised art circuit as a feeding battleground of survival for non-Western artists working within Western consumer capitalism. Encountering a “premature death without ever having a chance to live”[31], Huang’s installation was censored by animal protesters before exhibiting at Art and China after 1989: Theatre of the World at the Guggenheim Museum in 2017. Under ceaseless pressure from animal rights protests, the Guggenheim decided to only exhibit the panoptic gladiatorial enclosure without the animals present. Despite its “premature death”[32], the speculative work propels us to consider the possibilities of transcending the limitations imposed by culture and history because of Western globalisation. Confronted with the forces of cultural negotiation, migration, economic change, and survival within the global artistic utopia, Theatre of the World unveils the uneven power dynamics and dialogue that underpins Western consumer society. Remade 24 years later, Theatre of the World continues to reflect the sustaining conditions of the global art arena for cross-cultural and transnational artists. Cultural anthropologist Arjun Appadurai observes that “if a global cultural system is emerging it is filled with ironies and resistances”[33], with that in mind, Huang forces us to question the critical possibilities of a truly ‘global culture’ resisting the homogenisation of Western globalisation. Theatre of the World was a philosophical installation that allowed for new imaginaries of a New Internationalism towards cultural hybridisation, a “dreamland that is no longer Western centric but […] open to differences of expression”[34]. The speculative cannibalism of Huang’s work elucidates to the entangled modes of expression and cultural articulation generated from the collision of cultures.

Figure 7. Below: Huang, Yong Ping. Theatre of the World. 1993/2017. Mixed media installation, wood and metal structure with warming lamps, insects and animals removed, 150 x 170 x 265 cm.

Above: Huang, Yong Ping. The Bridge, 1995, painted steel structure with bronze wire mesh, wood, warming lamps, electric cable, found faux-bronze figurines (patinized and painted), insects and animals removed, 320 x 1200 x 180 cm.

Figure 8. Huang Yong Ping, Vomit Bag, 2017, written statement, ink on airplane sick bag. Collection of Guggenheim Museum.

This written statement and reflection was written on the plane by Huang after he found out his performative work “Theatre of the World” was censored by animal rights protesters

Contemporary Chinese artists of 1980’s and 1990’s were at the forefront of a new global artistic epoch. It was an era of confrontation, exchange, negotiation, and survival. As they entered their new norm of globalised Western hegemony, cross-cultural artists began to search for new expressions to decentralise and de-territorialise notions of identity and culture. Predicated on the ceaseless movement and exchange, Huang Yong Ping and Xu Bing brought about a new global modality that connects the hybrid expressions and aesthetics of their local identity to a transnational and global framework. These artists stood between East and West and sought to build a New Internationalism that allowed for the heterogenous enunciation of cultural differences. Offering an alternative reality to the stagnant paradigms of Western understandings of art, their transformative works created an entropy within the system. As Papastergiadis succinctly articulates “hybridity demands a re-evaluation of the modes of cultural and political affiliation”[35]. In their own ways, Xu and Huang criticised the conditions and complexities of Western globalisation and the strenuous demands of ideology, propelled by ceaseless movement, exchange, and migration. Their oeuvre illustrates the multitude of forces that shape contemporary art, beyond the representations of nationhood and geography.

So, what now? How has the global artistic modality of cross-cultural Chinese artists transformed since the 1980’s and 1990’s? Mobility continues to play a profound role in the artistic practices and reception of contemporary Chinese artists. Today, there are thousands of Chinese artists who live in and out of China as migrants, diasporas, and cross-cultural practitioners. These practitioners contribute to the global dialogue of questioning the discursive power of international cultural-artistic exchanges and resisting the global Western capitalist hegemony. The invention of a truly globalised world continues to be a process, however, the recognition for heterogeneity, hybridity, decolonisation, and decentralisation has become a fundamental modality for mobilised and cross-cultural artists today. As Papastergiadis profoundly concludes in his book On Art and Friendship, “artists resist the way cultural hegemony is occurring through a form of spatial domination. In the face of the globalisation of space, artists shape space to produce a new kind of local experience”[36]. The art of contemporary diasporic, mobilised and cross-cultural artists are no longer understood as a result of displacement and dislocation, but rather, are seen as the product of continuous relationality, mediation, translation and bridging. Overturning the established Western modes and systems of art, Huang Yong Ping, and Xu Bing paved the way for contemporary Chinese artists today through their endless negotiation with hybridity in a self-established mid-ground between local and global, East and West, in and out.

[1] Hou Hanru et al., Huang Yong Ping : Bâton Serpent. (Milan: Mousse Publishing, 2015), 12.

[2] Hou Hanru, "Towards an 'un-unofficial Art': De-ideologicalisation of China's Contemporary Art in the 1990s." Third Text 10, no. 34 (1996): 40 doi: 10.1080/09528829608576593

[3] Birgit Hopfener, Destroy the Mirror of Representation. Negotiating Installation Art in the 'Third Space, Negotiating Difference : Contemporary Chinese Art in the Global Context. (Weimar: VDG, Verlag Und Datenbank Für Geisteswissenschaften, 2012), 65. https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.monash.edu.au/lib/monash/reader.action?docID=2069200&ppg=61

[4] Gao Minglu, Total Modernity and the Avant-garde in Twentieth-century Chinese Art. (London: MIT Press ; in Association with China Art Foundation, 2011), 311.

[5] Nikos Papastergiadis, “Hybridity and Ambivalence.” Theory, Culture & Society 22, no.4 (2005): 47. doi:10.1177/0263276405054990

[6] Anne Ring Petersen, "The Artist as Migrant Worker." In Migration Into Art, Migration Into Art. (Manchester University Press, 2018), 95.

[7] Hou, Hanru, “From “Exile” to the Global : 2000 As the Theme.” In On The Mid-Ground, edited by Hou Hanru and Yu Hsia-Hwei, (Hong Kong: TimeZone8, 2002), 143.

[8] Slavoj Žižek, The Sublime Object of Ideology. (London: Verso, 2008), 29.

[9] Hou, "Towards an 'un-unofficial Art': De-ideologicalisation of China's Contemporary Art in the 1990s", 37.

[10] Hou, 40.

[11] David Clarke, "Contemporary Asian Art and Its Western Reception." Third Text 16, no. 3 (2002): 238. Doi:10.1080/09528820110160673

[12] Hou, "Towards an 'un-unofficial Art': De-ideologicalisation of China's Contemporary Art in the 1990s", 40.

[13] Clare Harris, “The Buddha Goes Global: Some Thoughts Towards A Transnational Art History.” Art History 29, no.4 (2006): 699. Doi:10.1111/j.1467-8365.2006.00520.x

[14] Hou, Hanru, and Gao, Minglu, “Strategies of Survival in the Third Space: Conversation on the Situation of Overseas Chinese Artists in the 1990s.” In On The Mid-Ground, edited by Hou Hanru and Yu Hsia-Hwei, (Hong Kong: TimeZone8, 2002), 67.

[15] Hou, Hanru, “Entropy; Chinese Artists, Western art Institutions: New Internationalism.” In Global Visions : Towards a New Internationalism in the Visual Arts, edited by Jean Fisher and Institute of International Visual Arts, (London: Kala 1994), 83.

[16] Petersen, The Artist as Migrant Worker, 60.

[17] Wu Hung, “Ruins, Fragmentation, and the Chinese Modern/Postmodern” In Inside Out: New Chinese Art, edited by Gao Minglu, (Berkley; Los Angeles; London: University of California Press. 1998), 62-63.

[18] Wang Chunchen, “The Art of Anxiety: China's Social Transformation and the Uncertain Reception of Chinese Contemporary Art” Journal of Visual Art Practice 11, no. 2-3 (2012): 223. doi: 10.1386/jvap.11.2-3.221_1

[19] Jeanne Boden, Contemporary Chinese Art : Post-socialist, Post-traditional, Post-colonial.

(Brussels : Academic & Scientific Publishers, 2014), 140.

[20] Boden, 143.

[21] Britta Erickson, Xu Bing, and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, The Art of Xu Bing : Words without Meaning, Meaning without Words. (Washington, D.C. : Seattle: Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution ; University of Washington Press, 2001) 62.

[22] Homi K Bhabha, The Location of Culture, (London ; New York: Routledge, 2004), 50-55.

[23] Harris, The Buddha Goes Global: Some Thoughts Towards A Transnational Art History, 699.

[24] Papastergiadis, Hybridity and Ambivalence, 43.

[25] Bhabha, The Location of Culture, 55.

[26] Petersen, The Artist as Migrant Worker, 93.

[27] Petersen, 93.

[28] Boden, Contemporary Chinese Art : Post-socialist, Post-traditional, Post-colonial, 196.

[29] Stine Høholt, “Reverse Cannibalism: Introduction to India: Art now”, In India: Art Now, ed. Christian Gether et al., (Ostifildern: Hatje Cantz, 2012), 32, quoted in Anne Ring Petersen, "The Artist as Migrant Worker." In Migration Into Art, Migration Into Art. (Manchester University Press, 2018), 101.

[30] Papastergiadis, Hybridity and Ambivalence, 39.

[31] Huang Yong Ping, Vomit Bag, 2017, ink on airplane sick bag, Guggenheim Museum. https://news.artnet.com/market/huang-yong-ping-gladstone-gallery-1259480 This written statement and reflection was written on the plane by Huang after he found out his performative work “Theatre of the World” was censored by animal rights protesters (see Figure 7)

[32] Huang Yong Ping, Vomit Bag, 2017, ink on airplane sick bag, Guggenheim Museum.

[33] Arjun Appadurai, Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalisation (Minneapolis; London: University of Minnesota Press, 1996), 29.

[34] Hou, Hanru, “On the Mid-Ground: Chinese Artists, Diaspora and Global Art” In On The Mid-Ground, edited by Hou Hanru and Yu Hsia-Hwei, (Hong Kong: TimeZone8, 2002),78.

[35] Papastergiadis, Hybridity and Ambivalence, 59.

[36] Nikos Papastergiadis, On Art and Friendship. (Melbourne: Surpllus, 2020), 245.